Hunting Montana Sapphires

Early June saw me flying to Helena, capital city of Montana, USA to participate at the second international gemmological conference organised by my gem friend Branko Deljanin FGA. The trip consisted of three parts: the multi day conference in a Helena hotel; visits to the primary and several alluvial sources of Montana sapphires and a visit to a ‘heater’ of local mined sapphires; then recreation time spent around Montana including a visit to Yellowstone Park.

I recall soon after joining the London laboratory in the late 1970s the director, Mr Farn, pulled me away from my diamond work (my early career was devoted entirely to the quality evaluation, or grading, of polished diamonds) to show me laboratory samples of sapphires from various global localities- particularly their colours and characteristic inclusion patterns. I learnt sapphires from Montana owing to their flattened tabular crystal shape are usually fashioned as rounds, many possessing rounded crystal inclusions appearing to the uninitiated as “ bubbles” and on examination under a microscope the crystals displayed a surrounding thin film halo or decrepitation halo. The finest examples of sapphires from Montana have a steely blue hue rich in tone. I grew to love the beauty of sapphires, particularly the rarer ‘no heat’ kind. Examples of which I trade today in Hatton Garden.

Early on during my Montana trip I learnt of a dichotomy in naming sapphires from that US state. Those mined underground at the primary source in the Yogo Gulch are known as ‘Yogo sapphires’ whereas sapphires extracted from the number of secondary alluvial sources are known simply as ‘Montana sapphires’; these latter crystals usually need heat treatment to bring out attractive hues of greenish blue, blue and the occasional pink. I was determined during my trip to secure examples of both “no- heat” Yogo sapphires and heated Montana sapphires. I was to succeed in my quest.

The conference party I joined had an international flavour being made up of the organisers, jewellery valuers (appraisers in American lingo), retailers, gemmologists, gem traders and one hobbyist. I counted representatives from six countries.

Our first sapphire mine visit was to the Yogo Gulch - a gulch being a local term for a steep ravine. Within the gulch is the primary source of sapphires - a dike of volcanic rock. Less than about one to six metres wide and a length believed to be about 10 kilometers long the dike has been mined sporadically since 1896 along multiple separate segments. Our conference group assembled in the Sapphire Village near the dike to meet our guide and mining specialist George Lind of the Roncor Corporation. Soon we were driven to multiple sites along the dike travelling east to west when we found ourselves at the Yogo Creek and our chance to mine sapphires.

The eastern end of the dyke. This area was first mined by an English company up until the 1920s

Significant underground production has occurred in a small area from both sides of Yogo Creek. The American mine on the east of the creek and the Vortex mine on the opposite bank. We visited both mines.

This photograph shows the area of the American mine on the east bank of Yogo Creek. Note the cleft where the Yogo Gulch cuts through the limestone cliffs.

A conference participant gathers sapphire bearing gravel from the walls of a Yogo mine.

It was fun for the group to enter a horizontal mine tunnel, hack material from its walls into large buckets then by the Yogo Creek sieve, wash and pick out the lustrous sapphire crystals from the gravel.

On the following day the group visited secondary deposits along the Missouri river. Here sapphires are extracted from terrace gravels along a 35 km stretch on both banks of the river. At least seven individual sites, called bars, have been mined for sapphires and gold.

A view of the Missouri river and mining on a bar.

At several mines we witnessed the mechanical extraction of sapphire crystals from the gravels, involving passing the gravels through screens, trammels and sets of jigs, washing and finally hand picking of the sapphire crystals.

Loading the mined gravels.

transporting the sapphire bearing gravel to the jigs.

Jigs separate the sapphire crystals from the gravel

These methods reminded me of the basic historical methods of diamond extraction I taught in my diamond tutoring days. Many of the mines sell bags of gravel to tourists to try their luck at picking out sapphire crystals.

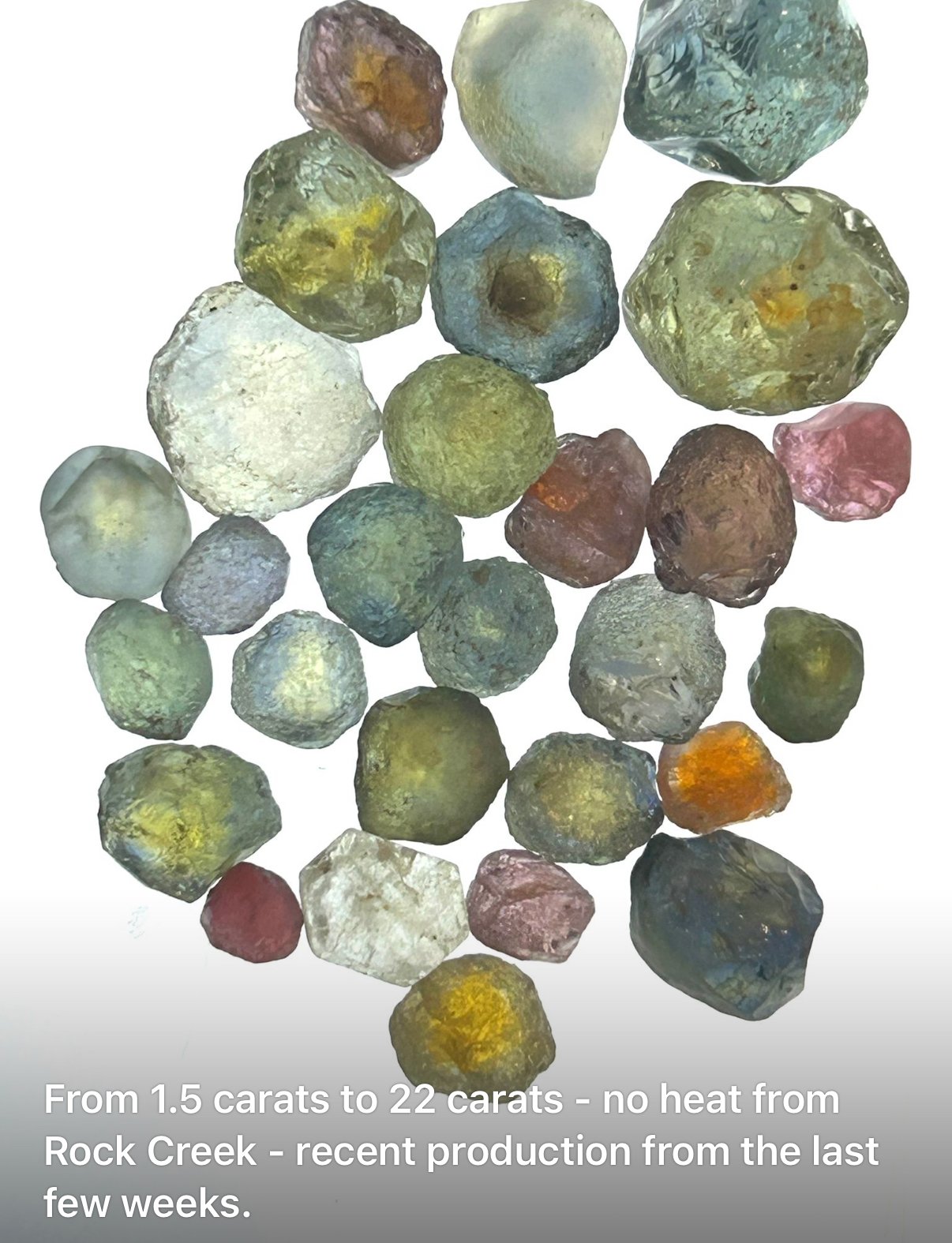

We visited another secondary source at Rock Creek near the town of Philipsburg on a subsequent day. First stop was a trip to the Rock Creek Sapphire Mine office operated by Potentate mining, where our guide Warren Boyd explained the operation and we witnessed the sieving, washing and hand picking of sapphire crystals from gravels transported from the mine.

Washing the sapphire bearing Rock Creek gravels

Warren Boyd of Potentate Mining explaining to our group how the sapphire crystals are sorted

Note the typical shapes and colour of the sapphire crystals I picked out.

At the mine at West Fork Rock Creek we saw the highly mechanised extraction methods of screening, trammelling, jigging and water extraction on a greater scale than other mines we visited. It is considered that over 1200 hectares (3000 acres) in this area,‘The Meadow’, can be exploited in the future.

Loading the mined Rock Creek gravels on to a hopper to be transported to a trommel

One of the trommels separating the sizes of the gravels

A pair of jigs separating sapphire crystals from the gravels

A view of part of the highly mechanised extraction plant.

The sapphire crystals extracted are cleaned with acids and ready for sale by tender in Bangkok. The crystals range of colours from bluish green, greenish blue and occasionally to pink and purple.

Note the colours of the sapphire crystals prior to heat treatment. Photo: Warren Boyd/Potentate Mining.

When sold, specialised heat treatment transforms the crystal colours to deeper blues, yellows and pastel hues. Heat treatment can also improve crystal transparency. I was interested to learn the primary source of these alluvial deposits is currently unknown.

We had time to visit in Philipsburg a shop selling gifts associated with locally mined sapphires and in its back room we were shown by local sapphire heating specialist Dale Siegford a kiln he uses to heat treat Montana sapphires to improve their appearance.

Crystal morphology, size, colour and inclusions

As mentioned earlier, Montana sapphires from both primary and secondary sources, are found as flattened tabular crystals, those from secondary sources show degrees of abrasion and rounded edges. When faceted most gems are cut as round brilliants and are less than one carat in weight, a two-carater gem would be extremely rare.

Yogo sapphires have a blue hue varying from faint to vivid in saturation, sometimes pink, purple and colour change stones are sometimes recovered. Alluvial crystals are mostly bluish green to greenish blue needing heat treatment to intensify the blue hue. Colour distribution throughout the crystal is even, lacking any colour banding. Crystals from both sources are of high clarity appearing clean to the unaided eye. The primary inclusions seen under microscopic examination are the decrepitation halos mentioned earlier. Noteworthy is the lack of ‘silk’ inclusions of rutile so common in sapphires from Sri Lanka, Burma and other geographical origins. These properties make for an easier decision when deciding Montana origin than with sapphires from other countries.

The gemmological conference

The conference provided an opportunity to learn and appreciate many aspects of gemmological topics. We heard from well known consultant gemmologist Lore Kiefert who has decades of experience in working for many of the most respected gemmological laboratories. Her workshop dealt with the treatment and origin determination of sapphires as well as the characteristic inclusions of sapphires from various geographical localities. For the practical element more than 50 samples from various origins and treatments were shown, most accompanied by photographs of their characteristic inclusions.

Warren Boyd, marketing director of Potentate Mining, the operator of the Rock Creek mine we later visited, outlined the extent of past and present sapphire mining in Montana, particularly the Rock Creek mine, previewing the extraction methods we saw at the site. The company is the largest producer in the state. Since its discovery in the late 1800s Rock Creek has produced over 65.8 tons of sapphire rough, approximately 90% of all sapphires from Montana.

Our group visited three of the four Montana sapphire mining sites.

The sapphire theme continued with a talk by well known consultant gemmologist Lore Kiefert who has decades of experience in working for many of the most respected gemmological laboratories. Lore spoke of the methods, instrumentations and problems of determining the geographical origin of gem quality sapphires from Kashmir, Burma, Sri Lanka, Madagascar and basaltic deposits in Thailand/Cambodia and Australia. The advanced laboratory methods to aid origin determination, such as UV-VIS spectroscopy, FTIR, EDXRF and LA-ICP-MS analysis were covered.

Another blue gem we learnt more about was turquoise. Joe Dan Lowry, whose family has been involved with the turquoise trade for years runs the Turquoise Museum in Albuquerque, New Mexico. His presentation covered how to grade quality and value various examples shown.

Joe Dan Lowry presents his talk on turquoise.

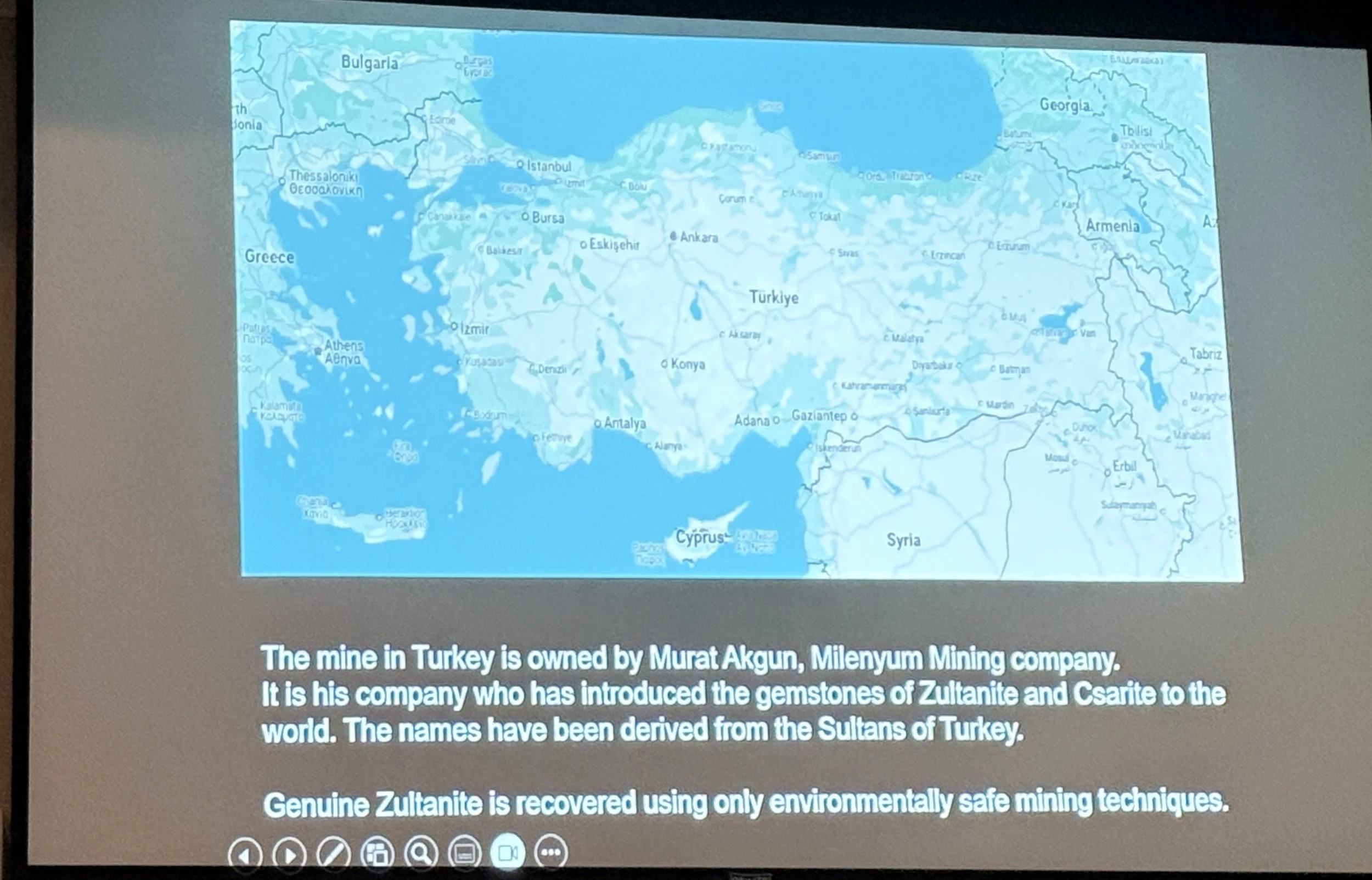

From Turquoise to Turkey where colour change diaspore is mined, Fazil Ozen, a fourth generation gem dealer, owner of Harmony Gems based in Hatton Garden and Istanbul, Turkey, spoke of Zultanite, a trade name for colour change diaspore. He informed us of its mining and marketing and showed rare examples of a cat’s-eye and bi-colour gems. Renowned for its colour change from green to pink under different lighting conditions, Fazil demonstrated the beauty of the gem and the ethical and environmental considerations of its mining.

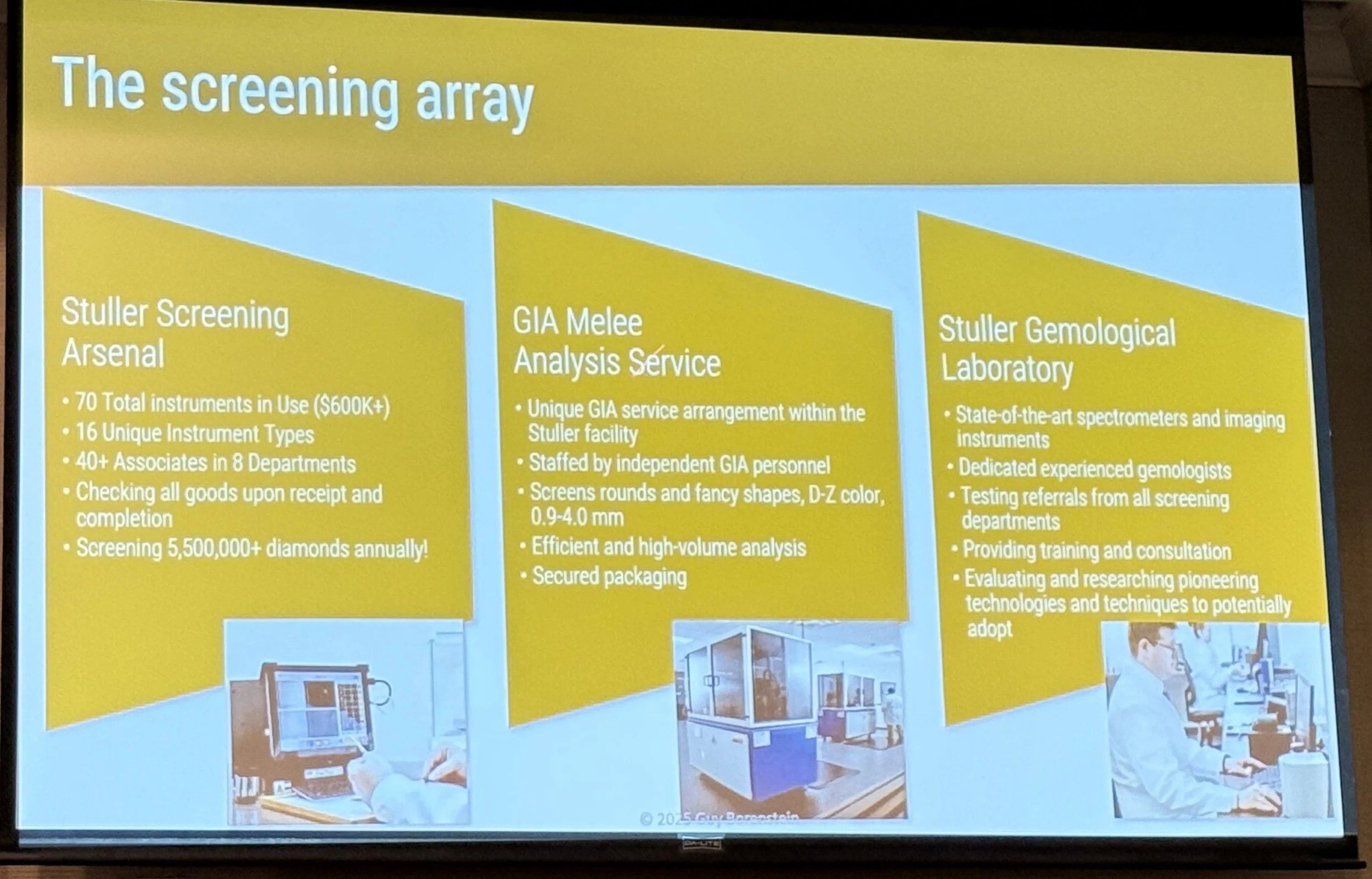

Following the lunch break, a presentation on the current availability of instruments for screening laboratory-grown diamonds (i.e. synthetic stones) was offered by Guy Borenstein, director of gemstone procurement and senior gemmologist at the US jewellery company Stuller Inc. His presentation covered each instrument's limitations as determined by Stuller’s screening tests investigations.

The diamond theme continued with Sharrie Woodring, senior gemologist at GCAL by Sarine gem laboratory, speaking of recent development on diamond traceability, market dynamics and diamond grading using artificial intelligence.

Traceability is gaining widespread attention owing to current U.S trade sanctions and increasing interest from retailers wishing to strengthen the narrative of natural diamonds through transparent sourcing.

The conference organiser, Branko Deljanin, informed us about the production, treatments and cutting of CVD grown synthetic diamonds in India. Based on a recent visit to Surat and its CVD grown diamond factories Branko described how the country has emerged as a leading producer of CVD grown synthetic diamonds and is home to numerous processing and cutting centres for both synthetic and natural diamonds.

We returned to Montana sapphires when Cynthia Shaver, a gem and jewellery valuer, emphasised the factors affecting the accurate appraisal of Yogo and Montana sapphires.They are valued for their US origin and historical importance. Market dynamics and trends, particularly those driven by demand for responsibly sourced and untreated gems have positively affected the pricing of sapphires from Montana in recent years.

The first day of the comprehensive conference ended with a couple ‘round table’ discussions on ‘Sapphire and Turquoise Origins’ and ‘Lab Grown vs Natural Diamonds”

The following day was given over to workshops where we had the opportunity of handling turquoise samples and its imitations,to learn how to grade turquoise quality and determine value using Joe Dan Lowry’s turquoise grading system.

Later we learnt during Branko’s workshop how to identify HPHT-grown synthetic diamonds using portable instruments and how to recognise the appearance of CVD-grown synthetic diamond when viewed using cross-polarised filters and ultra-violet lamps and how to identify some ‘overlapping’ type IIa natural and CVD-grown synthetic diamonds that need further testing. The workshop gave an opportunity for us to use the DOVE instrument by Gemetrix and the REVEAL instrument by JTR, both based on using deep short-wave and EXA by Magilabs using PL (365nm) spectroscopy.

Branko Deljanin assists Diane Chesler, a jewellery valuer, and Briana Daugherty, a jewellery retailer, both based in California, in his synthetic diamond workshop.

The knowledge I gained from my time in Montana was extensive, not only from the mine owners and workers, and a local gem specialist on the local sapphires during our field trips to the various mines but also on varied gemmological topics from the speakers at the conference.

Production volumes are tiny compared with the many current global sources notably from Madagascar and Sri Lanka yet sapphires from Montana are an enduring example of an American precious stone which I believe deserve greater recognition for their beauty by the global gem trade.

The next International Gemmological Conference is planned for 25 - 27 March 2026, to be held in Dubai and Bahrain. More details from https://www.gemconference.com/contact

Photographs by author unless otherwise indicated.

A condensed and edited note of this blog appears in the latest Journal of Gemmology (Vol 9, No. 7) 2025.

On Air

In this episode of the Paul Zimnisky Diamond Analytics Podcast, I chat to Paul, an independent data analysis and consulting proprietorship specializing in the global diamond industry, about distinguishing natural from man-made diamonds, how the gem-grading industry has changed, a few famous diamonds I’ve come across and a note on my favourite coloured stone. Listen here

‘Sustainability’ in the Gem Trade

Let’s look at that word Sustainability. Its concept within the gem trade covers the efforts to minimise any environmental impact, work to ensure fair labour practices, and encourage transparency in the precious stone supply chain from sourcing, cutting and polishing, to trading. With the growing consideration of climate change, human rights issues and preservation of the environment, gemstone buyers and producers are increasingly conscious of the wider implications of how gems are mined and traded.

Environmental Impact of Precious Stone Production

The environmental effect of gem production is clearly linked to mining activities; creating a hole in the Earth of any size to extract gems will affect the mining site. The extraction of gemstones, both coloured stones and diamonds, may involve processes that may lead to deforestation, soil erosion, and water pollution. Additionally, large scale mining is energy-intensive and can contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. Open-pit mining, common in coloured stone extraction, may have long-term consequences for the landscape and biodiversity around the mine. Thus reducing the environmental effects of mining has become a focus for sustainability efforts.

Ethical Sourcing of Gems and Labour Practices

The gem trade also faces social challenges related to the geographical sourcing of precious stones. In some countries, gem mining operations have been reported where unsafe working conditions, use of child labour, and human rights violations occur. So called “blood diamonds”, more properly called conflict diamonds, gained global attention in the late 1990s for their role in financing armed conflict, especially in parts of west Africa. Efforts to tackle these concerns include global initiatives such as the Kimberley Process, which aims to prevent the international trade in conflict diamonds. However, the effectiveness of such programmes may vary, and disquiet about effective enforcement remains.

CIBJO, the World Jewellery Confederation encourages that best practice is observed by the gem and jewellery trade through its Blue Books and its Code of Ethics”1, its Responsible Sourcing Book2 and its “Do’s and Don'ts” Guide3 that relate in part to the correct description of gemstone quality and any gem treatments applied. I attend annual CIBJO conferences and follow their best practice guidelines. The National Association of Jewellers (NAJ) in the UK, to which I am a member, has published several Codes of Practice including Diamond Terminology Guidance4, Gem Description Guidance Note5 and Environmental Claims Guidance Note6.

It is a fact that many of the regions that have traditionally produced the finest examples of coloured stones traded today are governed by unpalatable regimes. I trade demantoid garnets, only the finest from the Ural mountains of Russia. I trade non-treated red spinels and rubies from Burma (known as Myanmar). Both countries currently are not shining examples of liberal democracies respecting the rights of citizens. So should I not offer precious stones sourced from these countries? I do because I know trading the gems I source does not aid the current rulers of these countries. I acquire stock that I know have not been mined recently by sourcing gems from antique jewels, a form of recycling fine gems. Sometimes I purchase from international dealers who can assure me their stock has not been mined recently.

Conclusion

The environmental, moral and economic considerations define the sustainability of the global gem trade. By trading gems that are not new to the market and adhering to ethical standards as promoted by the various trade organisations I endeavour to reduce its negative impact and contribute in my small way to a more responsible gem trade.

References:

CIBJO Code of Ethics https://cibjo.org/code-of-ethics/

CIBJO Responsible Sourcing Blue Book https://cibjo.org/ethics-and-sustainability-resources/

CIBJO Do’s and Don'ts Guide https://cibjo.org/dos-donts-guide/

NAJ Diamond Terminology Guide https://www.naj.co.uk/write/MediaUploads/Resources/NAJCOP-DiamondTerminologyGuide-v2.pdf

NAJ Gem Description Guidance Note https://www.naj.co.uk/write/MediaUploads/Resources/NAJGuidanceNote-Gemstone2024.pdf

NAJ Environmental Claims Guidance Note https://www.naj.co.uk/write/MediaUploads/Resources/NAJGuidanceNote-Gemstone2024.pdf

Let’s Talk Diamonds!

When you start to think about diamonds first understand what is meant by the word ‘Diamond’

Just remember three things.

Diamonds are formed deep within the Earth, 900 million to three billion years ago, brought to the surface by natural forces millions of years ago and mined in only a few places on the Earth’s surface. Some may call diamonds ‘natural diamonds’ or ‘mined diamonds’.

Artificial diamonds can be manufactured in factories using two methods; within machines which create the extreme heat and pressures needed to grow them or in machines which use methane and other gases to grow them. Such products may be called ‘lab grown diamonds’, ‘laboratory grown diamonds’, ‘synthetic diamonds’, ‘man-made diamonds’, ‘created diamonds’. Other terms have been used. Artificial diamonds and diamonds have the same chemical make up, the same optical properties of lustre, brightness and ‘fire’, and the same physical properties of hardness, toughness and density.

There are artificial products that look to the eye at first sight like diamonds but do not have the chemical, optical or physical properties of diamonds or artificial diamonds. These products are called simulants. Examples are glass, rhinestone crystals, cubic zirconia and moissanite.

Global trade associations advise the word diamond should only be applied to those formed in the Earth.

Artificial: “made or produced by human beings rather than occurring naturally, especially as a copy of something natural”

Blog - Diamond Beauty (2) - ‘Life’.

Let’s look at light reflected from a diamond. If you are wearing a diamond (lucky you!) or can see a diamond near you, take a very close look at it now. Without moving the diamond, see if you can see how ‘shiny’ it is, how light is reflected from its surface.

When scrutinising the diamond can you discern its flat surfaces, called facets? There are many having various shapes, varying sizes and are arranged in a symmetrical pattern called the facet arrangement. We shall see later the sizes, pattern and angles between facets contribute greatly to the beauty of diamond.

You see your face when looking in a mirror because all the light falling on it from your face is reflected from the flat mirror surface back to your eyes. When light falls on a diamond almost all enters the gem through the top (crown) facets but a surprising amount doesn’t, it’s reflected back. Some of this reflected light reaches your eyes; you see the facets as shiny surfaces.

How much light is reflected from a gem’s facet in relation to the amount of light falling on it is called reflectivity. Diamond has many superb characteristics as a gem, one of them is its high reflectivity. So high, that when light falls on a diamond facet almost a fifth doesn’t enter the gem, it is reflected back to our eyes creating the ‘shininess’ so loved by many diamond admirers.

Let’s use the word ‘life’ in place of ‘shininess’. We shall see later that the size of the largest facet on top of a diamond, the table facet, greatly influences the amount of ‘life’ of a diamond.

You may have heard the word lustre. Gemmologists use it to describe the appearance of a gem’s surface when it reflects light. Diamond has such a high lustre compared to other gems it has its own unique description: ‘adamantine’ lustre. Most other gems have a glass-like or ‘vitreous’ lustre. The unique lustre of diamond is due in part to its extreme hardness; no other gem comes close to being as resistant to being scratched by other materials. Its superb hardness means it takes an extremely flat facet surface when cut and polished from the uncut ‘rough’ crystal. A very flat facet makes for a great reflecting mirror surface.

Summary:

Diamond is so shiny due to its superb physical (hardness) and optical (reflectivity) properties. Shininess or ‘life’ is seen as light reflected off the crown facets of a diamond. Life is just one component of the famed brilliance of diamond. Most of the light falling on a diamond enters the gem. We shall consider this in the next blog.

Diamond Beauty (1)

Today let’s start exploring the subject of Diamond beauty.

Most jewellery-set diamonds lack colour. They are essentially colourless. Not the entrancing red of ruby or spinel, the calm blue of sapphire or tanzanite, or the arresting green of emerald or demantoid garnet.

Diamond beauty, revealed to our appreciative eyes, lies not in colour but in brilliance.

If you have handled or more probably seen images of unpolished diamond crystals, referred to as rough diamonds in the trade, they look like shiny pebbles. Take a look at my Instagram pic at https://www.instagram.com/p/B_mWInDFMzK/. Yet they are shinier than crystals of other gem varieties but not as much as polished diamonds https://www.instagram.com/p/B_mllfElRw5/

The ‘shininess’ of a diamond is one of their appealing characteristics and part of the makeup of its brilliance. Diamonds display a greater degree of shininess than most other gem varieties.

Why are diamonds so shiny? The answer is in the manner the polished gem interacts with light. Light is essential to display diamond beauty. Two effects can occur when light falls on the flat surface (facet) of a polished diamond; either it is reflected back, shown by this black diamondhttps://www.instagram.com/p/CAus95hFRSh/ or it enters the gem.

In my next blog we shall look at light reflected from a diamond.

Salt and pepper diamonds

I started learning about diamond quality and grading in the late 1970s. At that time in Hatton Garden the clarity system used and taught was not the one formulated by the GIA, now universally utilised, but one predating the American system. Towards the lower end of the clarity scale were the Piqué grades, First, Second and Third Piqué (abbreviated P1, P2, P3). Pique is a French adjective meaning dotted (I was taught it meant ‘pricked’) referring to the spotted appearance of the many eye-visible inclusions within the diamonds. Below the Pique grades were the rarely utilised grades Spotted, Heavy Spotted and Rejection - terms used by a number of cutters and dealers for qualities thought so poor that they had little commercial appeal.

Early on I learnt the Scan DN grading system that listed 1st Piqué, 2nd Piqué and 3rd Piqué was the lowest clarity grades (I considered this system the finest to learn, a grading book illustrating each grade with numerous diagrams was published aiding the tyro diamond grader). CIBJO grading terms introduced in the UK forty years ago had similar low grades of P1, P2 and P3 equivalent to the GIA grades of I1, I2 and I3 (the letter I for Included, although originally GIA used the word Imperfect)

Whatever clarity terms were employed to describe these diamonds containing eye visible light and dark crystals, fractures (feathers) and clouds, such low-grade gems were deemed unattractive so cheap to buy. Yet currently there is a growing demand from jewellery designer-makers for diamonds with ‘character’, ones with unusual and unique characteristics, those displaying obvious inclusions. In the place of the terms Pique or I3 one sees the phrase ‘Salt and Pepper’, referring to the sprinkling of inclusions arguably resembling grains of pepper and salt. A marketing ploy using a catchy phrase to make low grade diamonds appealing.

My video on my Instagram feed shows three such ‘salt and pepper’ diamonds. Gross weight is 1.96 carats, the mid sized diamond is 5.7mm. All are untreated. From my teaching collection I used to show diamond students the appearance of I3 clarity diamonds.

Contact me if you are interested in buying. Smaller similar quality diamonds are available.

Post-Covid buying

How was your Covid lockdown? Are you a little more confident to emerge and get back to a degree of normality? Even if it’s the ‘new normal’?

You’ve probably spent less cash on a daily basis since mid March. Now you wish to spend a little. To loosen the purse-strings a little - a beach holiday perhaps? Of course not - who wants to be confined in a metal tube with strangers for hours? Not a smart move. OK, so spend more on gadgets? Really? How many gadgets do you need, particularly as they are throwaway ‘toys’ you’ll be bored with after a short time?

I’m seeing a movement where folks after enduring months of lockdown are reappraising their lives and wishing for more lasting experiences, emotions and gifts. Many are looking to buy for themselves long lasting jewellery as a reward, a feelgood symbol, a memento of coming through lockdown, celebrating this time now as a marker to remember the immediate past and a beautiful jewel to keep as they look to a better future.

Let me know what you are planning to buy as a reward in the next few months.

Diamond Beauty

Imagine the last time a diamond caught your eye.

Perhaps another person was wearing one at a socially distanced event or workplace. Or your best friend has shown you her diamond engagement ring. Or you have seen a diamond in a jeweller’s shop window as you walked by. Now ask yourself what attracted you to the gem? Was it the size of the diamond? Or its shape? Or something else?

Tell me what excites you about diamond beauty. Comment below.

We shall explore this topic in future blogs.

Any Questions?

Why are you visiting my website today? Perhaps you’ve seen a post of mine on one of my social media accounts? Or your web search has directed you to me? Whatever the reason, you must curious about gems and jewellery.

Perhaps you are a consumer researching a gem or jewellery purchase or you are in the trade wishing to learn more about current trends. Or a journalist looking for some background facts for your next story. Whoever you are, let’s chat.

Go to the Contact page (the link is in the header above) to start our conversation.

Gemmology - what’s that?

It all begins with an idea.

I was at home during week 1 of the UK lockdown due to the COVID19 pandemic, on my terrace enjoying the sun chatting to neighbours in adjacent gardens and balconies. The talk came round, as it usually does when talking to others for the first time, to what we do for a living. One neighbour was a lawyer, others a dentist, a yoga teacher, a non-executive director and business school students. In turn I was asked what I do. “I’m a gemmologist”, I replied to my quizzical neighbours. ‘What’s that?’ said one.

Let's define the word. Gemmology is the study of gems. Wikipedia has “gemmology is the science dealing with natural and artificial gemstone materials.” Note in the US the spelling is gemology.

In the 19th century it emerged as a branch of mineralogy, the study of minerals; most gems are attractive, durable and scarce varieties of minerals (a few gems have an animal (e.g. coral and ivory) or vegetable (e.g. jet and amber) origin. We shall see how the sciences of geology, chemistry, analytical physics and biology are also encountered within gemmology.

I’m a gemmologist. A professional gemmologist. My career has been one of identifying gems and their treatments (Gem Identification) and judging the quality of polished diamonds (Diamond Grading). When I started work in the London gem laboratory in the late 1970s the prime task when testing a gem, whether a diamond or a coloured stone, was to determine its authenticity. That is if it had a natural origin (from the Earth) or if artificial, grown by Man, to look like a natural gem. Pearls were tested to distinguish the rare natural pearl from the more common cultured and imitation pearl.

During my career the testing of a gem developed to include the identification of any treatments to the gem to enhance its beauty hence value. Most gem varieties are routinely treated; various chemical and physical processes are employed to improve colour and clarity. The identification of many modern gem treatments is now more challenging to the gemmologist than testing gem authenticity.

Lately, identifying the geographical (and sometimes the geological) origin of a gem has gained commercial importance as ‘country of origin’ affects the value of some gem varieties. The gem trade attaches more value to scarce fine examples of Kashmir sapphires, Mogok, Burma rubies and Colombian emeralds. Determining where a gem was mined is challenging for a gemmologist demanding the expert use of specialised laboratory instrumentation. Today, the jewellery buyer is asking where and how a gem and the precious metal of a jewellery item has been mined and whether sourcing and trade commerce was transacted in a responsible and ethical way.

To carry out the tasks of a gemmologist, one needs to acquire a thorough knowledge how gems form in the Earth (and how their man-made counterparts are grown), their crystal form, the chemical makeup of the gems, their physical properties, such as hardness, toughness, density and optical characteristics, particularly refractive index, and their behaviour when subjected to various spectroscopic and elemental analysis.

Yet gemmology can extend beyond all these analytical tasks, beyond the physical sciences to art, history, economics and other disciplines. The history of the use of gems in jewellery through the ages and as shown in art since the fifteenth century, their symbolic relevance to diverse cultures; the geology and geography of gem deposits in the world, the economics and social responsibilities of exploration, mining, distribution and pricing of gem materials, the history of gem cutting (lapidary) and of global gem trade routes and marketplaces, all add to the rich field that is modern gemmology.

Do you have a question about gems or gem-set jewellery? Get in touch so we can start a conversation.